Hot Right Now

Alien “city” found on the Moon state Ufologists: Here is how to find it...

Is it possible that there are alien structures on the Moon? Or what if, the Moon itself is an Alien structure? For over 20 years, people have debated whether there is something anomalous with Earth’s natural satellite, now it seems that after all, the Moon is filled with surprises.

According...

Researchers reveal 143 new Nazca Lines of strange humanoid beings and a two-headed ‘snake’

YouTube Video Here: https://www.youtube.com/embed/dm_7AEycc8k?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1

A team of researchers from Yamagata University, along with IBM researchers, has found 143 new Nazca Lines in Peru with the help of A.I. technology. One small geoglyph of a 'humanoid' was found using A.I technology alone for the first time. Among these never-before-seen formations are...

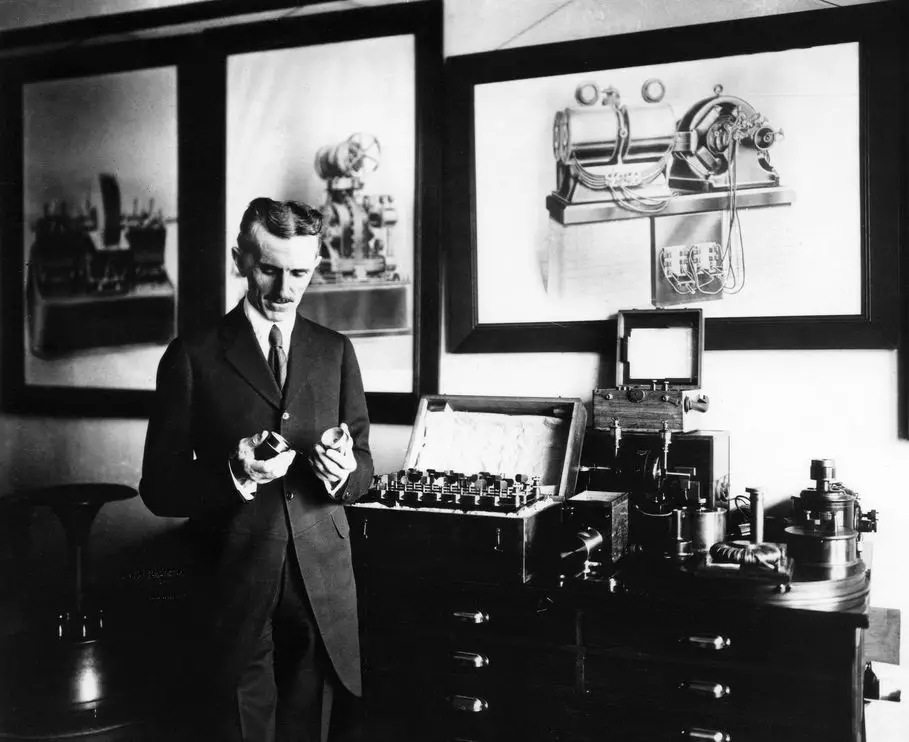

The extraterrestrial Messages of Nikola Tesla

Tesla believed he received alien messages at the end of the nineteenth century

It is not a secret that there are numerous inventions of Tesla that have been attributed to other "inventors", among these inventions are the radio and the first machine capable of searching for extraterrestrial life. The...

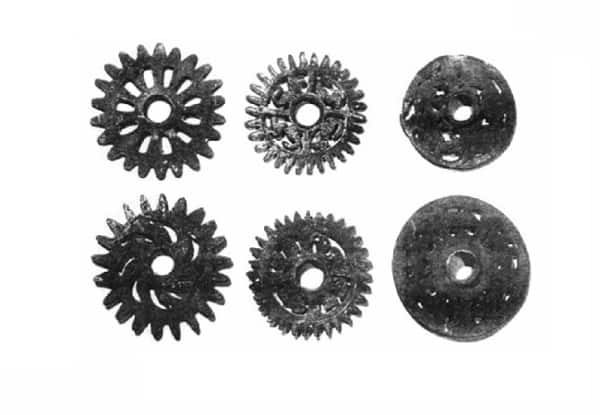

The Mechanical Gears of Ancient Peru: Keys to the ‘Gate of the Gods’

The Ancient Gears of Ancient Peru fit the description of the legendary 'Key' that would open access to the 'Gate of the Gods' at Hayu Marca.

The 'Bronze Gears of Ancient Peru', or 'Gears of Ancient Peru' are considered by many as one of the most mysterious artifacts discovered in...

Atlantis, Tiahuanaco and Puma Punku; Incredible Similarities

Atlantis in... Bolivia?

According to many researchers Atlantis might have been located in the American Continent, and some believe that the Bolivian Andes region coincides with Plato's description of the lost continent/city of Atlantis. In his work Timaeus and Critias, Plato describes a huge continent called Atlantis where an advanced...

CLE 2017 Reveals: Secret Space Programs, Aliens, and Inner Earth Civilizations

YouTube Video Here: https://www.youtube.com/embed/5-ff_Rnv47k?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1

Inner Earth beings... "They're a fourth-density being, and apparently they trace their lineage back to the Earth, and some of them, including the Anshar here, back 18 million years."

During the Conscious Life Expo 2017 in LA, Corey Goode revealed fascinating details about secret space programs, Alien...

Trending

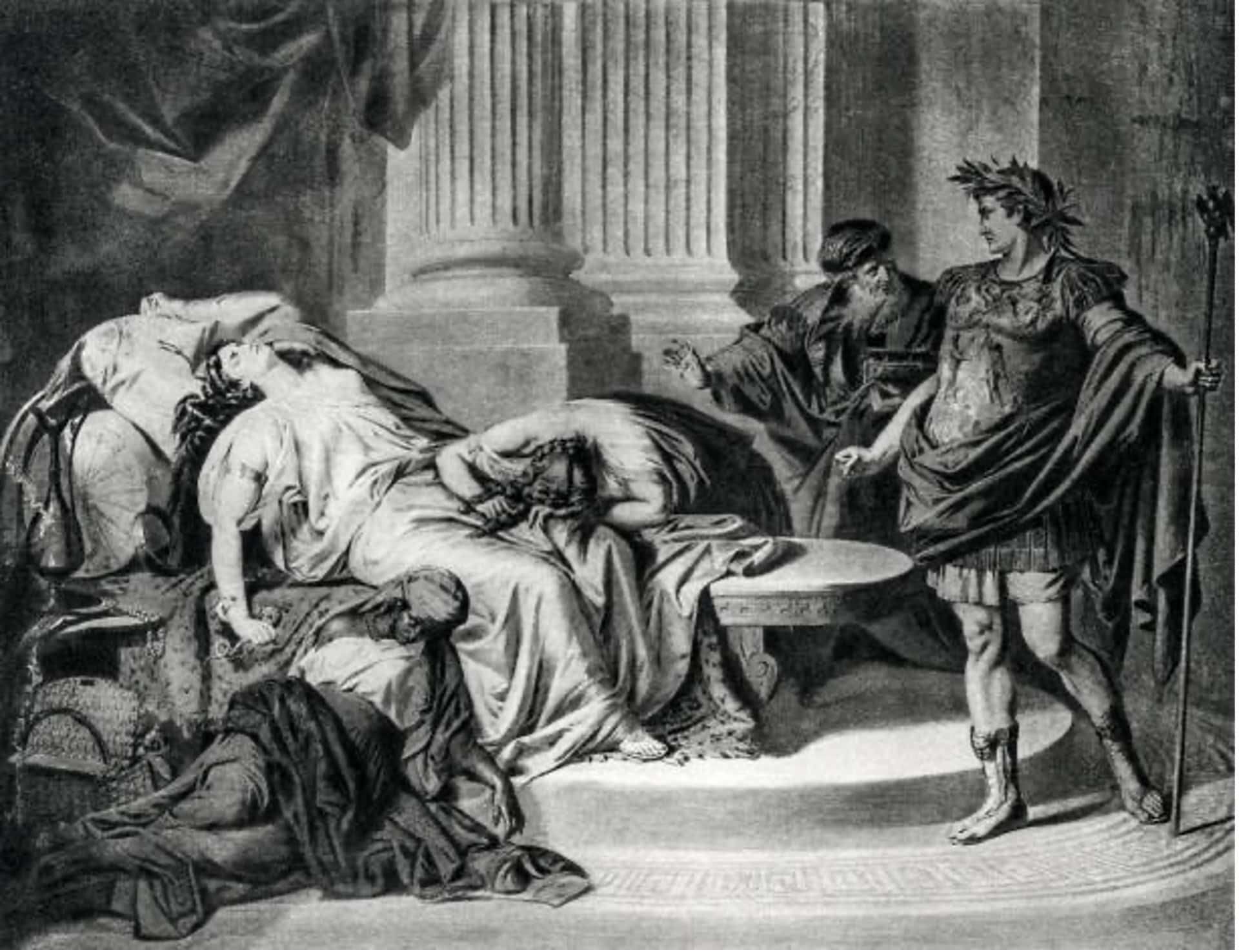

cleopatra

How did Cleopatra die?

Cleopatra VII the queen of Egypt and one of the most famous women in history. Cleopatra rules over the prosperous Egyptian empire. She is beautiful, intelligent, and a master of manipulation. Every man she meets falls in love with her, including Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

Over time, Cleopatra's ambitions...

What did cleopatra look like?

Cleopatra, the Queen of Egypt, was one of the most renowned figures of her time. She was a beautiful, intelligent, and charismatic personality that used her power and influence to shape the course of history. However, her appearance and looks are still a mystery to the world as there...

Who was Cleopatra

When we hear the name Cleopatra, we think of a beautiful and alluring woman with a tragic story. But who was she? Cleopatra was the last active pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt and briefly survived as pharaoh by her son Caesarion. After her reign, Egypt became a province of the...

News

LATEST ARTICLES

The Chronovisor: A device used by the Vatican to look into the future and...

According to numerous reports and stories that have been published through the years, among the many alleged secrets the Vatican has, there is a device called the Chronovisor. The device enables its user to observe future as well as past events. Many believe this device is one of the greatest guarded...

Buzz Aldrin: We were ordered away from the moon

YouTube Video Here: https://www.youtube.com/embed/ZNkmhY_ju8o?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1

It sounds like a science fiction script for an upcoming movie about NASA, Astronauts, and aliens on the moon. However, according to several reports, and alleged transcripts between the command center and Apollo astronauts on the moon, mankind encountered otherworldly technology upon setting foot on the lunar...

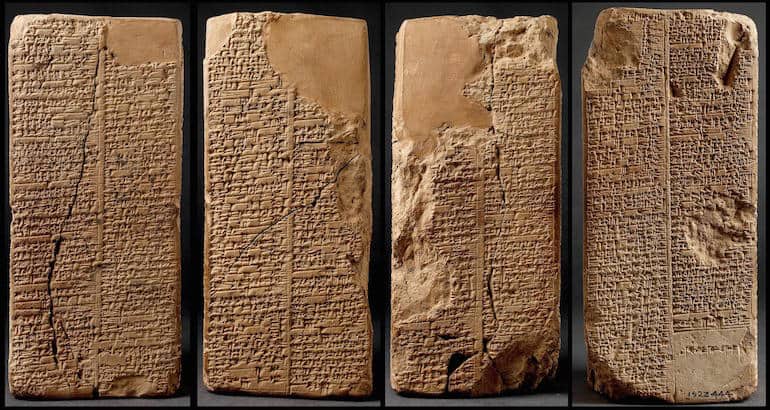

15 facts about the Sumerian King List: When gods ruled Earth

Among the numerous ancient texts, manuscripts and scrolls that completely disagree with mainstream history –or at least offer a complementary view— we find the ancient Sumerian King list which according to many is one of the most mysterious and important ancient texts ever discovered on Earth.

Why? Because it...

250,000-year-old artifact: The ultimate evidence of ‘Ancient Astronaut’ technology?

The discovery of an ancient artifact, mainly composed out of aluminum is considered as compelling evidence of 'ancient astronaut' visitations to Earth over 250,000 years ago. Lab tests have confirmed the age of the artifact and its mysterious composition.

The idea that humanity has been visited by beings not from...

In 1178, five Monks at Canterbury saw part of the Moon explode

"...Out of the middle of its division, a burning torch sprang, throwing out a long way, flames, coals, and sparks. As well, the moon's body which was lower, twisted as though anxious, and in the words of those who told me and had seen it with their own eyes,...

Do These 4 videos ‘prove’ the US has a Secret Space Fleet?

YouTube Video Here: https://www.youtube.com/embed/j8-f-9pjpC0?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1

In recent times, many people have come forward saying that there's more to NASA and space than we have ever been told. But are these just empty claims? Or is there something more to it? According to hackers, government officials and even former military personnel, there...

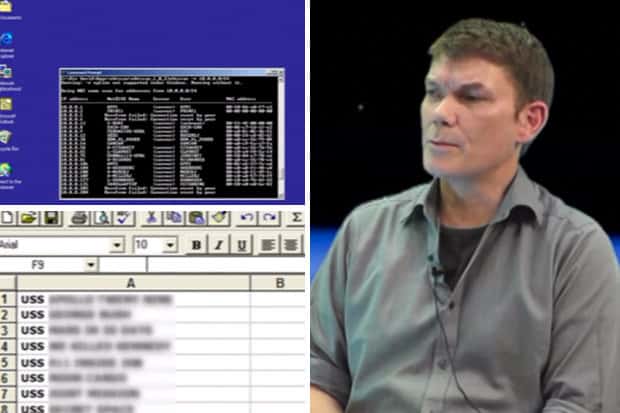

Secret Space Program Whistleblower claims Humans are on Mars since 70s

A secret space program whistleblower claims Humans have been traveling to Mars for decades. Interestingly, many former NASA employees and military officials have come forward speaking about the existence of a Secretive Space Program and technology that goes far beyond what society knows.

“There exists a shadowy government with its own Air...

Ancient Egyptian artifact found in Mexico confirmed as authentic

YouTube Video Here: https://www.youtube.com/embed/mn4vGBYQQqk?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1

A mysterious statuette discovered in Mexico has recently been confirmed as Authentic. The mysterious statuette dates back to the 19th dynasty and has ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs covering its surface. Researchers confirmed that the item discovered in Mexico is, in fact, an ancient Ushabiti figurine.

The ushabtis were funerary figurines...

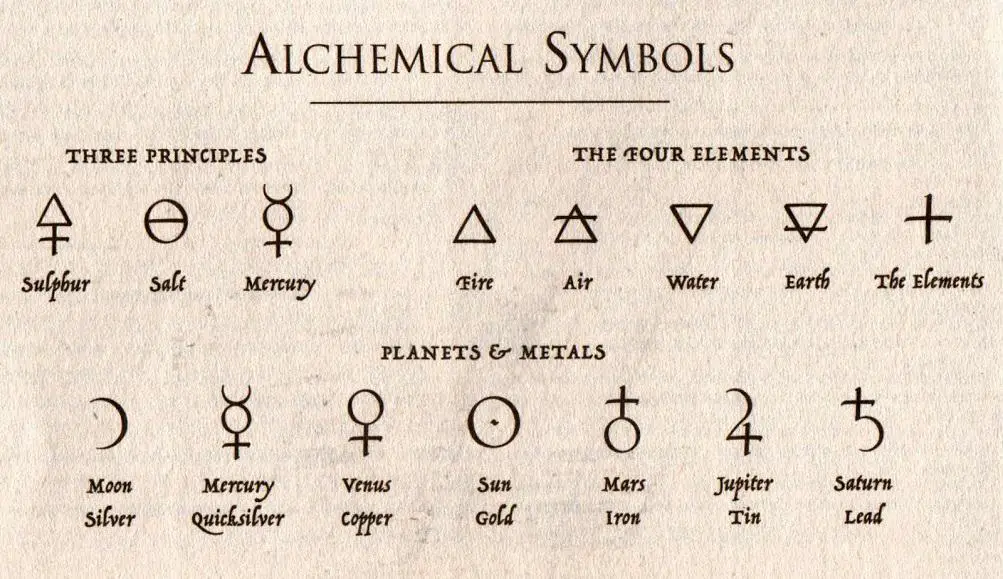

Alchemy, Isaac Newton, and the secret code of the number three

One of the most influential scientists of the 17th century was Isaac Newton. Newton introduced what became the basis of all modern physics: the three laws of motion, but what many people don’t know is the fact that Isaac Newton was an extremely mystic person and extremely interested in alchemy.

Found among his documents about philosophy, astronomy, and...

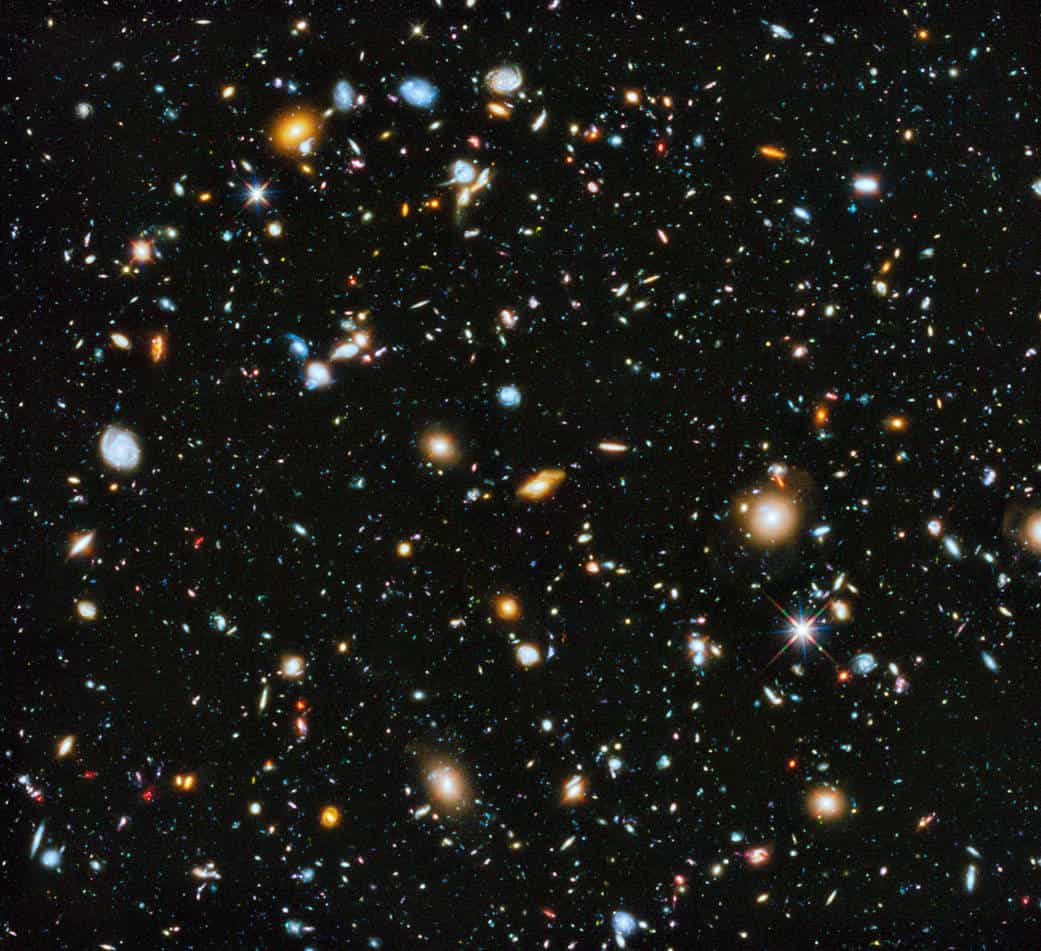

Universe has two trillion more galaxies than previously thought

Researchers have recently found that the observable universe is much larger than previously thought. According to a new study, the observable universe has two trillion more galaxies than researchers thought in the past.

One of the fundamental questions in astronomy is how many galaxies are there in our universe.

Astronomers had...